Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is the most common type of antibody in the human body. It plays a critical role in the immune system, helping to fight infections and maintain long-term immunity. IgG is produced by B cells and circulates in the blood and other body fluids. Here's a straightforward breakdown of how IgG works and why it's so important.

What is IgG?

IgG is one of five main classes of antibodies (others include IgA, IgM, IgD, and IgE). It is responsible for identifying and neutralizing pathogens like viruses, bacteria, and toxins. IgG makes up about 75% of the antibodies found in our blood, making it the most abundant antibody in circulation.

Once our immune system encounters a pathogen, B cells are activated and start producing IgG specific to that pathogen. This helps the body fight off the infection and provides long-term protection if the pathogen is encountered again in the future.

Main Functions of IgG

- Neutralization: IgG antibodies bind to viruses, bacteria, or toxins, preventing them from entering cells and causing infection. This process is called neutralization, as it stops the pathogen from spreading in the body.

- Opsonization: IgG can coat the surface of pathogens, making them easier for immune cells (like macrophages) to recognize and engulf. This process, known as opsonization, helps the body clear out harmful invaders.

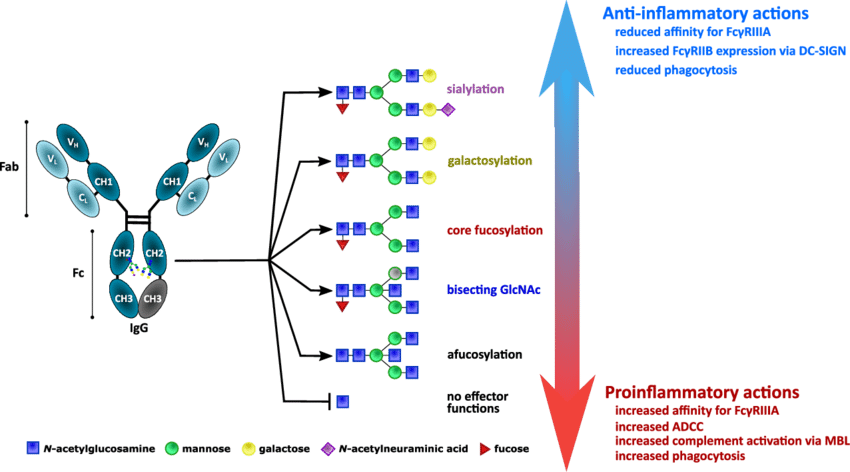

- Activation of the Complement System: IgG triggers the complement system, a group of proteins that assist in destroying pathogens. When IgG binds to a pathogen, it activates these proteins, which then work to break down the pathogen's membrane, leading to its destruction.

- Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC):

IgG helps direct natural killer (NK) cells to infected or abnormal cells. NK cells then release toxic molecules that kill these marked cells, which is particularly important in fighting viruses and cancer cells.

- Immune Memory: Once IgG is produced, it remains in the body for a long time, sometimes years or even decades. This allows for a faster and stronger immune response if the same pathogen reappears. This is how vaccines work—by prompting the body to produce IgG against a specific pathogen so that future infections are prevented or weakened.

Subclasses of IgG

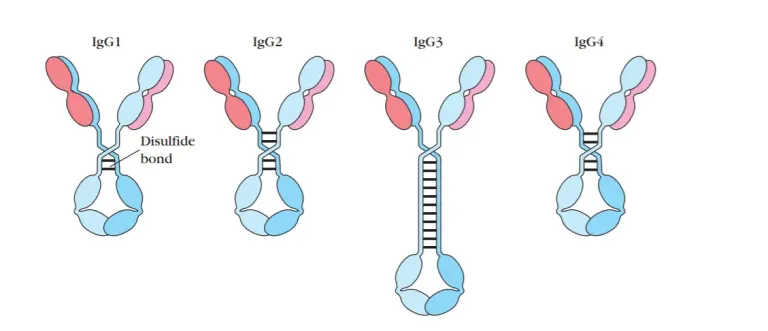

IgG comes in four different subclasses, each with specific functions:

- IgG1: The most common, effective against viruses and toxins.

- IgG2: Helps defend against bacteria with polysaccharide (sugar) capsules.

- IgG3: Activates the complement system strongly, helping in pathogen destruction.

- IgG4: Involved in regulating immune responses, often seen in chronic infections or allergies.

IgG in Vaccination

Vaccines rely heavily on IgG. When you receive a vaccine, your immune system produces IgG specific to the pathogen introduced by the vaccine. This IgG stays in your body, ready to fight off the real pathogen if you encounter it in the future.

IgG Deficiency

Some people have low levels of IgG, which can lead to frequent infections, especially in the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems. This condition is known as IgG deficiency. Treatment often involves immunoglobulin replacement therapy, which provides the body with the antibodies it lacks.